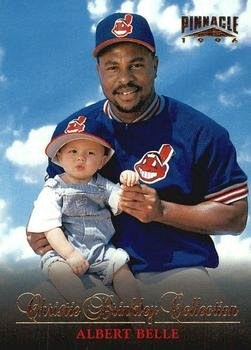

Albert Belle “Snapper”

The Tao of Rocky runs deep. On the surface, of course, those sacred texts seem like fables about grit and perseverance in the face of overwhelming obstacles. I suspect that, for many Americans born between 1950 and 1980, that Rocky is practically synonymous with “underdog.” But if you keep digging into Stallone’s six part opus -- past Apollo, through Drago, all the way to the other side -- the ideas get headier an the interpretations more complicated.

For three films, and into part of the fourth, Stallone meditates on the capacity of human change. Rocky repeatedly suggests that men like him -- fighters -- cannot change. Early in IV, however, he seems to unclench that resolve. He’s older. Wiser. Maybe it’s time to hang up his gloves. Apollo quickly snuffs out that thinking. The former Master of Disaster does not want to change — he likes who he is. Tragically, it was that inflexibility which ultimately got him killed. And so, eighty something minutes into the film, bloodied and draped in the red, white and blue, Rocky Balboa does an about face. With the help of a Russian translator, the champ howls about the magic of change. Soon after the film’s release, the Cold War eased — because of Rocky IV and its transformative message. And probably a couple of other things.

In Rocky III we got a frightening glimpse at the terrifyingly thin line between fact and fiction. When Rocky battles Thunderlips for hand to hand combat supremacy in a charity event, the distance between reality and performance is blurred to the point of imperceptibility. Thunderlips is, of course, played by WWE/F legend, Hulk Hogan. For children of a certain age, for whom the legitimacy of professional wrestling was already unclear, the appearance of the world’s most famous wrestler, under a new name, in a nominally different guise, was confusing enough. Rocky himself initially seemed assured that the battle was simply an act -- a put on. But, within minutes, the gigantic heel tosses Balboa into the crowd and begins assaulting uniformed police officers. And though the melee does magically resolve itself, and Rocky snaps a quick photo with the wrestler, the larger question lingers: what is real and what is not?

The Rockys examine countless philosophical matters. While not quite biblical in breadth or depth, they are perhaps the Iliads and Odysseys of the 1970s and 80s. Of the many questions posed, however, few are so deeply existential and painfully unanswered as those surrounding James “Clubber” Lang. Why did the greatest heavyweight of his generation -- a man who annihilated his class until he quizzically opted to stand in place and be pummeled by a wiry middleweight with feathered hair and Hawaiian Tropic tanning oil for lubricant -- never fight again? To the best of our knowledge, following his second bout with Balboa, Lang does not return to the ring. Why? Moreover, why was Clubber so angry? Why did he “live alone, train alone” and “win the title alone”? Underneath the mohawk and the feather earrings and the muscles, what could we learn about hatred and rage from Clubber Lang?

Because he never returned to the Rocky series and because Stallone and T have been terse on the subject, we have to read between the lines. Stallone once suggested that, after Rocky III, Lang found god and became a ringside announcer. Most Rocky scholars, however, are unconvinced by that facile resolution. My interest is less in the career arc of Lang and more in his motivation. Not “what” was Clubber, but “why” was Clubber? For that question, I referred to the old testament -- the first Rocky -- and to Tony Gazzo’s words. When the local mobster is attempting to diffuse a situation between his driver, Buddy, and his collector, Rocky, he says to the latter, “Some guys, they just hate for no reason. Capisce?” Is it really that simple? Are some men just born with hate in their souls? Are they unredeemable? Are they incapable of love? Were they wounded themselves? And, finally, do those feelings ever go away?

As much as I appreciate the financial services that Tony Gazzo provided to the greater Philadelphia area, I do not trust his explanation. But I knew where I might find answers. If I jumped forward a couple of decades and traveled northwest towards Lake Eerie, I could locate a baseball player with a heinous stare and a vicious swing. A man who destroyed baseballs with the fury of Lang’s right hand. A man who wanted to be left alone. Whose biceps burst from his uniform and who, with or without a bat in his hand, was seemingly capable of great violence. This man, of course, is former Indians’ (and White Sox and Orioles) slugger Albert Jojuan Belle -- the Clubber Lang of Major League Baseball.

Between 1991, when he became and every day player, and 1999, his last healthy season in the league, Albert Belle was, alongside Frank Thomas and Ken Griffey Jr., the best hitter in baseball. Belle had the most doubles, hits, RBIs and total bases of the trio during that span. He had the second most home runs and the second highest slugging percentage. They share virtually identical OPS+ numbers and can be separated primarily on the basis of WAR, which leans heavily in favor of Griffey, who was both a brilliant fielder and who played a position that was WAR-friendlier. During his twelve seasons in the league, two of which were as a back up, one of which was cut short by a strike and one which was impacted by a career ending injury, Belle averaged forty home runs, forty-one doubles and one hundred and thirty RBIs. Those are Lou Gehrig or prime Albert Pujols numbers. They’re somewhere between cartoonish and historic. But, obviously, Albert Belle’s story is more complicated than his numbers. To suggest that Albert Belle was the best hitter of his era is defensible, but highly debatable. To claim that he was the angriest or most hateful batter, however, is not up for debate.

Belle had an odd batting stance. He stood basically on top of the plate and leaned in even further. At times, his head appeared to be firmly in the strike zone. His angle was more closed than opened. His bat was cocked back and held still. He did not wiggle his body or his weapon. When he got set, he did not budge. Until the pitch was thrown, he cast a murderous gaze upon the pitcher. There is truly no better adjective for his expression. Albert Belle looked like he wanted to kill every pitcher he faced. If somebody glared at me the way he glared at Greg Maddux, I would probably call the cops. When he hit the baseball, he did so savagely. You felt bad for the ball. He did not uppercut. His home runs did not look pretty or like the natural outcome of swing trajectory. Albert Belle home runs traveled farther because they were hit harder. And when they stayed inside the park, they were generally doubles only because they were hit too hard and too fast to be triples. To this day, I’ve never seen a man hit a baseball with such anger as Albert Belle.

In 2000, however, after a markedly down season (twenty three home runs and one hundred and three RBIs), he suddenly retired. He’d missed several weeks that season, due to a nagging hip injury and, when rehab did not suffice and the prognosis sounded ominous, he walked away. He was thirty three at the time, just shy of four hundred home runs and without a World Series ring or MVP award. He’d gotten close. In 1995, the Indians made their first World Series in nearly fifty years, only to fall to the Braves. That same year, he finished second to Mo Vaughn in the MVP ballot, in spite of besting the winner in every significant offensive category and leading his team to a dozen more wins and a pennant. Belle finished third in the MVP race on two other occasions. He retired with very comparable stats to Kirby Puckett and Jim Rice -- both Hall of Famers and both of whom played in many more games. Albert Belle never garnered more than a 7% share of Hall of Fame votes. He was off the ballot in two years.

It is fairly easy to defend Belle’s greatness. There are many who steadfastly argue that he is a Hall of Famer. On the other hand, his rap sheet is long and his list of critics is practically endless. Albert never won a major award for a very simple reason: sports writers universally despised him. Following a USA Today hatchet job early in his career, Belle largely refused to speak with the media. He would offer an occasional interview to those few reporters he trusted. But generally he asked to be left alone -- especially during his batting practice, or after a loss. DiMaggio was given his space. So were Sandy Koufax, Steve Carlton and Eddie Murray. Albert didn’t understand why he was any different. He was both meticulous in his preparation and fixated on wins and losses. While reporters resented it, they necessarily stayed away. In the rare moments they did not abide or when they were coincidentally in Albert’s personal space, bad shit happened. During the 1995 World Series, a number of NBC reporters, including Hannah Storm, got too close to the slugger during his “me time.” Provoked or not, crazed or justified, Belle’s seething tirade was beloved by Indians’ fans and despised by everyone else. His legendary non-apology went:

"The Indians wanted me to issue a statement of regret when the fine was announced, but I told them to take it out. I apologize for nothing."

The “Hannah Storm incident” was, frankly, the slightest of misdemeanors compared to other hard to explain / harder to defend moments from Belle’s too short career. There was the time in college that he got suspended for going after a fan who was making racist comments. Though probably quite justified, this indiscretion got Belle flagged by scouts. Whereas he was considered a surefire first round pick -- possibly the second pick in the draft after Griffey -- he ended up going later in round two after LSU suspended him. There was the time in 1990 that he threw a baseball at the chest of a heckling Indians fan. That same year, he entered rehab, sobered up and adopted his birth name (Albert) in place of his lifelong nickname (Joey). The name change confused baseball card collectors and inspired more razzing from opponents. In 1994, Belle was suspended for corking his bat, an accusation he amazingly still denies, in spite of the considerable evidence. The next year, on Halloween night, he chased down a bunch of young, egg-hurling pranksters who were upset that Belle had no candy to offer them. He ended up chasing and then bumping one of the kids with his car and allegedly warned police:

“You better get somebody over here, because if I find one of them, I’ll kill them.”

The stories seem never ending. While with The Indians, Belle, who grew up in the interminable heat of Louisiana, demanded that the clubhouse temperature be set below sixty degrees. When Kenny Lofton dared to move the thermostat above seventy, Belle allegedly took his bat and destroyed the device. That one got him the nickname “Mr. Freeze.” In 1996, Belle took out Brewers’ second baseman Fernando Viña during a double play by running straight at him with his forearm. In 2006, years after his retirement, he was arrested and convicted of stalking a woman who was also a licensed prostitute. In 2007, he was evicted from an apartment in Italy for complaints of noise and drunken behavior. As recently as 2018, Belle was arrested near his home in Arizona for drunk and disorderly conduct. The mug shot -- like most mug shots, I suppose -- was slightly scary, but very sad.

Though he was called “Joey,” and then “Albert,” and occasionally, in derisive asides, “Mr. Clean,” the nickname that perhaps best suited Albert Belle was “Snapper.” He would just snap. Everyone knew it. He knew it. Many times over the years, it has been suggested that Belle took steroids — that his anger was a product of “roid rage.” To be clear, there is no proof whatsoever of this accusation. Albert Belle was a great hitter in every level of baseball he played. He grew more muscular, like nearly every player does as they fill out and are afforded access to more equipment and training. But he was not massive in the way McGwire or Bagwell or Canseco were. He was six foot two and two hundred and twenty pounds. He appeared to be basically the same size for most of his career. In interviews, Belle swears that he was terrified of the side effects of PEDs and that, frankly, he didn’t need them. And though his claims are in mild conflict with his bat-corking, based simply on what I saw, I tend to believe him. He half-seriously, half-resentfully explained his famous rage by saying, “I was just an angry Black man.”

In retrospect, the legendary Albert Belle stories make for good clickbait and great content. He was (and is) a grown man, responsible for his actions. However, Albert Belle -- the signifier -- is a construct steeped in bias. The truth is always much more complicated than the sum of the stories. And it's perhaps doubly so in this case. The story we never hear — the other version — starts this way: Albert Belle was an Eagle Scout. A merit scholar. He graduated sixth in his high school class. He’s the son of two educators, both with masters degrees. He’s a voracious reader. He claims to play ten thousand games of chess annually. For thirty years, he’s funded scholarships for Black high school students in Shreveport. He’s a proud father of three daughters, whom he dotingly drives to soccer practice and evidently takes great pride in. To the best of my knowledge, he is still very much married to his wife, Melissa, with whom he tied the knot in 2005. Now that he is retired, he also gives interviews. His recall for specific games and pitches is uncanny. He loves to regale in nostalgia, no more so than when talking about those great, mid-90s Tribe teams. He sounds inordinately polite, if completely serious. His love of the game is apparent. His former commitment to training and preparation sounds extraordinary. His tone is exacting and humorless. Having now read every Albert Belle interview I could find, what is now clear to me is that -- at least during his playing days -- the Clubber Lang of baseball viewed life in binary terms; right and wrong, winning and losing, hitting and pitching, the very best and the absolute worst.

I’m the father of tween girls. At a recent school conference, their teacher said, almost in passing, something like: “You’d better keep an eye on this one — she’s got a perfectionist streak.” Immediately, I tensed up, picturing Albert Belle’s 2018 mugshot. On the one hand, it’s hard not to be proud of a report cards full of good grades and examples of fine manners and surprisingly skilled art projects and adorably winning Monopoly games. Similarly, it’s amazing to be in a club with Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Fox and Albert Pujols (eight straight thirty homes, one hundred RBI seasons). It’s historic to be the only person to ever hit fifty home runs and fifty doubles in the same season. Winning feels better than losing. Professional sports is a game, but also -- yes -- high stakes competition. The will to win is useful, and it can be amazing. But it can also be lonely. You remember the misses more than the hits. You feel shame for all of the losses, especially for the times you struck out. And you absolutely remember every single slight. Every person who doubted you. You remember the time your college coach lied to you about playing in the College World Series. You remember when your minor league manager promised to promote you, but didn’t. You remember when the team’s general manager promised not to talk about your contract negotiations publicly, but leaked information to the press anyway. You remember that slight from your ex-teammates memoir. You remember everything.

Obviously, my daughter will never have the life that Albert Belle had. She’ll never play a professional sport. She’ll probably never get called a racial epithet. I doubt that she’ll ever assault another person. She’s a great kid. I love her endlessly. But, also, I know that she looks at many things as if they are a competition. That feels pretty normal and — within reason — not unhealthy. Quite rightly, Albert Belle viewed baseball as a competition. It is one. But, he also seemed to view it as a battle. And while there is something very primal and martial about a person throwing a ball very fast and very close to another person who is trying to trying to both defend himself and destroy that ball, sports are not actually battles. And they are certainly not wars. And they’re not a zero sum game. Sometimes the losers are happier than the winners. And sometimes the team that wins isn’t actually the best team at all. And all of the time, players -- even the greatest ones -- get older and struggle to play at their peak level. Most of them still soldier on -- for love of the game, or money, or camaraderie, or all of the above.

But not Albert Belle. While I have no idea if he was unable to physically play beyond 2000, I am convinced that he was constitutionally unable to do so. To go out there and hit .250 with a dozen homers and seventy RBIs was unfathomable. To lose that many more battles was sickening. It would be not unlike getting knocked out in three rounds by a tiny man who trained in a yellow half shirt while running on the beach.