Dan Quisenberry “Poetic Relief”

It’s 1985. I’ve just started the sixth grade — still completely a boy and not even remotely a man — and I’ve already had enough of middle school. Too many new kids. Too much homework. The towering eighth graders. The first signs of cliques. All of it. But, most of all, phys ed. I — who had always loved gym class, who never missed a chance to join a pickup game of any kind — was suddenly sick to my stomach with fear of phys ed. Or, more specifically, fear of my gym teacher, Mr. Diana, who was six feet of granite and fury, stuffed into ass-grabbing shorts, a pit-stained t-shirt and a whistle. He’d begun the year with an immaculate bowl shaped haircut, parted perfectly down the middle. But then, one day, as if he was daring us to giggle, he walked into class with a tightly curled perm. The image of that man — so angry, yet so permed — was more terrifying than anything any of us had ever seen in the movies. There were no giggles. No one said a goddam word.

Gym class was split by gender. The girls would normally stay inside where they would presumably receive a normal physical education while the boys would be taken out to the fields where Mr. Diana would hit scalding line drives at our terrified mitts and throw irate spirals into our scrawny chests. The first time he asked me to run a short slant pattern, the football was on my neck before I even had time to turn. The sheer force of the throw knocked me to the ground, where I lay for a moment, teary eyed, embarrassed and catching my breath. When I eventually stood up, Mr Diana said, “Gary, that was pathetic. I don’t know why I even bother throwing to you.” In my three years of middle school, I never let him know that my name was not, in fact, Gary.

Between algebra and hormones and lunch table anxiety and — mostly — Mr. Diana, I just needed some relief. Fortunately, I discovered it in “The Baseball Bunch,” my primary respite from the horrors of middle school. “The Baseball Bunch” ran most weekends during the spring and summer, right before “This Week in Baseball,” which immediately preceded the “game of the week.” And if you were a boy of a certain age, interested in baseball, music videos and silly pranks, “The Baseball Bunch” was a flawless media product. It was hosted by hall of fame catcher, Johnny Bench, who was surprisingly deft and telegenic, and included weekly guest spots by the dugout wizard, played by Dodgers’ manager, Tom Lasorda.

“The Bunch” was eight kids of assorted sizes, colors and genders, plus one oversized chicken (“The Chicken”) who operated as mascot, comic relief and, astoundingly, spot starter for their pitching staff. And while his talent on the mound was dubious, his sense for hijinks was not. Each episode of the show was designed around the same basic structure. A (current or former) major league star would join Johnny and The Bunch for an instructional segment, which would be broken up, first, by The Chicken’s silly antics and, then, by a montage of baseball highlights played against a contemporary pop song. Then, the gang would get back together to practice what they had learned in the first segment, then more antics plus probably one more montage. And then, finally, the dugout wizard would send us off with his parting words of wisdom. Twenty one minutes each week. Thirty with commercials for Kool Aid. It was never anything less than perfect.

“The Baseball Bunch” ran for roughly six seasons, from 1980 into 1985. There seem to have been about forty episodes in total, though that figure is hard to verify, on account of the complete lack of surviving evidence. Though there is a solid Wikipedia entry for the show, there is no online episode history. Youtube only offers ten or so full episodes and the IMDB page is mostly blank. You can buy a compilation VHS on eBay (I’m not saying that I have, but I’m also not not saying that I have), but that is only a “best of” program. There’s a loving oral history that Sports Illustrated did in 2016, but it is short on stats. Nearly forty years later, it’s astonishing to think that a show which once featured sixty year old Ted Williams removing his fisherman’s coat so that he could drill line drives off a pitching Chicken would simply disappear.

And yet, for the most part, that is exactly what has happened. In spite of the magic of Youtube and the glut of steaming services, I cannot press play and watch middle-aged, three hundred pound Willie Stargell hit the ball five hundred feet over the heads of ragtag little leaguers from Arizona. I can’t watch Phil Niekro, who was forty-ish at the time but looked not a day younger than seventy, teaching The Chicken how to throw a knuckleball. There are so many episodes that I’d love to watch alongside my son right now. But the one that I don’t actually need to see, because I completely memorized every shot and every word of it back in 1985 when it imprinted itself upon me, is the Dan Quisenberry episode.

Following an ad for Trix or Count Chocula, we hear that familiar theme song — a jaunty 80s rocker that makes its convincing case early and often: “We’ve got a hunch/You’ll like the Baseball Bunch.” Then, after the cast is introduced and one more ad for a sugary breakfast cereal, we cut to the ninth inning of a ballgame. The Bunch is up three to one but the Saguaro Sharks are threatening. Two men on and “The Incredible Bulk” is up to bat. Andy is called in to pitch in relief for The Bunch. He’s shaky with nerves, understandably so given the size of his opponent. He tentatively throws his first pitch right down the middle where The Bulk meets it and deposits it a mile away, over the center field fence. Sharks win, four to three.

It turns out that the game was just a dream — Andy’s nightmare, really. When he wakes up, he is greeted by the rest of The Bunch, alongside Kansas City Royals’ ace reliever, Dan Quisenberry. And from there, we’re off. Next, “Quiz” teaches the kids how to stay cool under pressure, followed by an MLB highlight montage played against (obviously) Billy Joel’s “Pressure,” followed by a hilarious sketch wherein The Chicken dons shades and tries his hardest to act cool, followed by a demonstration of Quisenberry’s unusual throwing motion, followed, finally, by the actual Sharks versus Bunch game. It’s the bottom of the ninth once again. But this time, it’s no dream. Andy comes in to pitch and, with the benefit of advice he received from the Royals’ star, he retires The Incredible Bulk on a lazy ground ball to short. The Bunch wins, five to two.

So, why this episode — why is this the one that stuck with me? Some part of it is probably recency bias. It ran later in the series, during a time from which my memories are particularly vibrant. Also, it featured a short segment in which Quisenberry tries to remain calm while facing the one batter he fears the most — my hero, Eddie Murray. Finally, there’s the fact that the episode is about the one thing which I desperately craved in 1985 — relief. In small ways, it’s all of those things. But, mostly, it’s on account of the guest star. Dan Quisenberry was perhaps the most unusual man to ever play major league baseball.

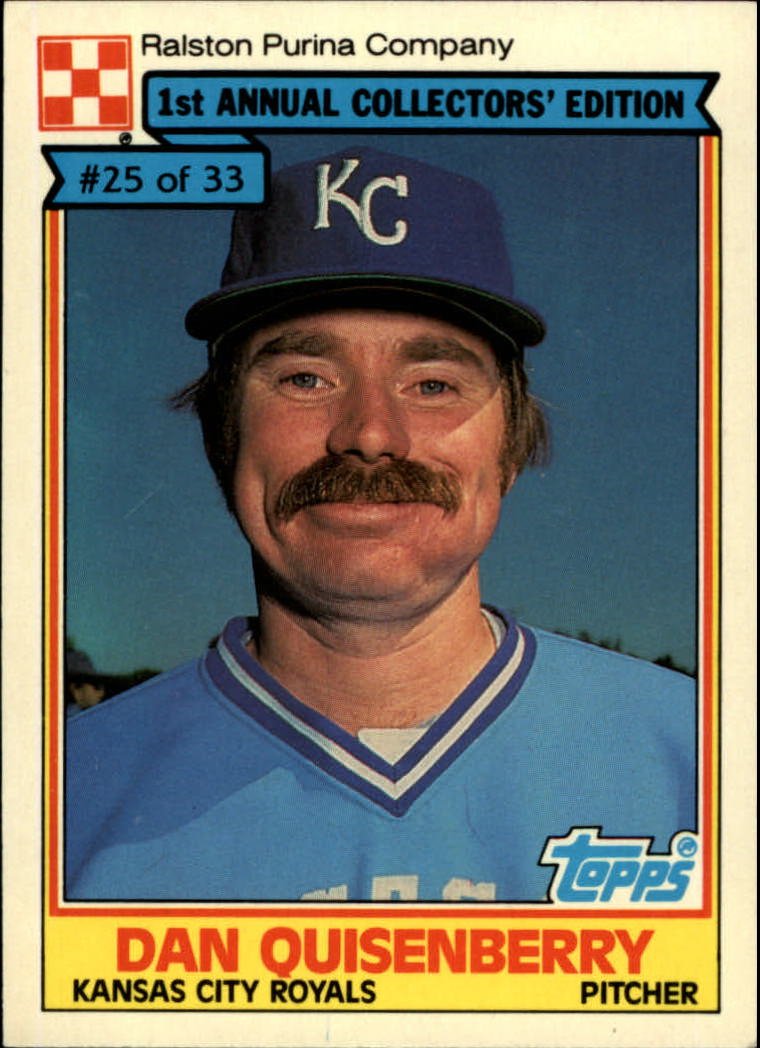

Quiz was not physically exceptional. He was tall — six foot two — but in no way gigantic. He looked the opposite of imposing, like somebody who spent much more time reading than working out. His hair was brownish red and thinning up front. And his mustache was thick, wide and furry. Frankly, it was adorable. Whereas Rollie Fingers’ stache was a cursive distraction and Goose Gossage’s was pure intimidation and Dennis Eckersley’s was surprisingly handsome, Dan Quisenberry’s mustache looked like the fourth member of Alvin and The Chipmunks. It intimidated literally no one.

That was kind of the thing with Quiz. He was just different. Relief pitchers were supposed to look menacing like Al Hrabosky. Baseball players were supposed to be either fast and fit, like Rickey Henderson, or big and strong, like Jim Rice. But Quiz was none of those things. He seemed bookish, if oddly athletic. He appeared more like the guy who would double as a middle school gym teacher and English teacher. I would have traded every baseball card in my collection — even the Eddie Murray rookies — to swap Mr. Diana for Dan Quisenberry.

If he looked a little odd out there in his uniform, though, it was nothing compared to his delivery. Dan Quisenberry was one of a very short list of players who threw a true submarine pitch. Submarine pitchers had been a rare, if beloved, part of baseball for decades. Infamously, Yankees pitcher Carl “Sub” Mays, who’d achieved great success on account of the pitch, killed Guardians’ shortstop, Ray Chapman, when his errant submarine fastball struck Chapman in the head. Years later, Ted Abernathy became one of the game's first great short relievers on account of the pitch. And, in the 1970s, durable, bespectacled Pirates’ reliever, Kent Tekulve, built a stellar career thanks to it. Tekulve taught It Quisenberry how to throw the pitch. But it was Quisenberry who perfected it.

Though he only adopted the submarine style late in his minor league career and though he initially only had one version of the pitch — a slow, sinking fastball — Dan Quisenberry was a fast learner. By the end of 1979, he’d added a curveball and slider to his arsenal. And, by 1980, just his second year in the majors, he was the most effective relief pitcher in the major leagues. Saves, a statistic that had been born in the 1960s and had come into vogue in the later 1970s, were highly coveted by the time Quiz came of age. And between 1980 and 1985, no pitcher — not Fingers nor Sutter nor Gossage — had more saves than Dan Quisenberry.

During that stretch, he won the “Rolaids Relief Man” award five times and finished in the top three of the Cy Young race four times (placing fifth one other year). Unlike most of his peers, however, he did not save games with blazing speed or power. His fastball never approached ninety. He struck out only three batters per nine innings. But his control was historically great. If you discount the intentional variety, Quiz walked far less than one batter per nine innings. Instead, he let hitters hit hard ground balls to Frank White and lazy fly balls to Willie Wilson. In spite of his unusual delivery, hitters routinely described feeling very comfortable at the plate against him. And yet, they’d inevitably finish a series confused with their 0 for 4 performance against the reliever, while Quisenberry would keep his ERA around a tidy 2.00.

When his sinker was working, Quiz would drag the fingernails of his right hand as close to the ground as possible, while kicking his right leg nearly two yards out from the pitching rubber. Just as that right foot was landing, he’d then literally hop his left foot two feet over, and somehow regain perfect balance. All of this was happening while the ball was moving up and then down, or up and to the left or, in the case of his occasional knuckler, up and who knows where. The pitches were slow enough for batters to nominally adjust, but also vexing enough to ensure that they induced lackluster swings.

As much as his motion engendered success, so did his personality. Quisenberry was witty and affable, upbeat and honest. He was a man of faith and service who was beloved not just by teammates, but by most of the league. That affection was something of an edge, making it easy for hitters to underestimate him and harder for them to do battle. Sports writers quickly caught on. Enamored of his humor and quotability, they began filling news pages with quotes like: “I became a better pitcher when I found a delivery in my flaw.”

Quisenberry’s unlikely success led him to an appearance on “The Tonight Show” and, in 1983, a “lifetime contract” with The Royals, which guaranteed the reliever tens of millions of dollars over its term. Then, finally, in 1985, with the help of George Brett, Bret Saberhagen, Willie Wilson, Steve Balboni and Charlie Leibrandt, The Royals defeated the Cardinals in the World Series. 1985 may not have been his best season statistically, but it was certainly the apex of his baseball career. It was also the beginning of the end.

Between 1986 and his eventual retirement in 1990, Quiz could still be effective. But he was less consistent, which is the antithesis of what teams need from their closer. Moreover, it seemed that he’d lost some of the drive. There was so much more to life. He knew it. And he was ready for it. After his playing days, he did the things that pitching kept him away from — being a husband, a father, a man of service and a poet. Yes, a poet. In 1998, he published his first book of poems, entitled “On Days Like This.” By any standard, but especially for a former ballplayer, the book represented a lyrical and insightful achievement. “Time to Quit,” for example, is about the gutting end of his playing days:

i’m warming up in san Francisco

you see

it’s a damp wind-off-the-water cold

and i’m trying to throw sinkers

into this gale force

the ball

a sparrow in a hurricane

barely makes it

i reach back and grunt

whip it in there like the old days

but i’m a salmon swimming up river

a doberman gnaws my shoulder

with each toss

and i keep seeing the letter

my daughter

wrote inside a crayoned tear drop

saying “come home”

skip’s out there on the mound

looks back at me

i want to be invisible

don’t want to play anymore

just an advil

a shower

and a quick flight home

The same year that his book was released, Dan Quisenberry was diagnosed with a malignant, inoperable brain tumor. Several months after the diagnosis, George Brett went over to his former teammates house to check in and begin to say farewell. According to Brett, when he asked, “Why you?” the poet slash submariner responded, “Why not me? I can handle this.”

Dan Quisenberry died on September 30, 1998 at the age of forty-five. When I heard Dan Patrick announce the news on SportsCenter, I was out twenty-four and a foot taller than the kid who watched “The Baseball Bunch.” I was done with school. Mr. Diana wasn’t the scary monster any more. He was just a character in a coming of age story that I joked about with friends.

The obituaries for the pitching poet were loving and sad — really, really sad. Each time they aired on ESPN, which was hourly for a day or two, I choked back a little something. Surely, I could handle it. That’s what I told myself. Obviously, he was gone far too soon. Clearly, the world was better with him around. However, it wasn’t as though we were friends. He was just a guy I knew from baseball cards and USA Today box scores. Whatever little I knew about him, there were volumes more that I’d never know. Except the one thing: that we all need some relief sometimes. And Dan Quisenberry provided that.