Dave Parker “The Masked Cobra”

By 1975, Hank had surpassed The Babe. Willie had spent a couple seasons with The Mets and walked off into the sunset. Frank Robinson was player-managing, with an emphasis on the latter. The golden age of baseball was behind us, fading into a color closer to brownish mustard.

In the wake of our heroes’ departures, we were left with a motley crew of sluggers. Reggie was supremely fun, but also a .275 hitter whose star exceeded his stats. Michael Jack Schmidt was amazing but he had a perm. George Foster was the guy who’d hit fifty-two homers — an unthinkable number in 1977. But it was hard to imagine a guy with a twenty-nine inch waist ever making a run at five hundred. Luzinski was “The Bull,” but his glasses made him look like a rec softball ringer. Kingman was as towering as his bombs but, most of the time, he could barely put the ball in play. Winfield was just as tall as Kong and twice as talented, but he played for The Padres. The Padres! So, that left two guys: Jim Rice, the young phenom from Boston, and Willie Stargell, the beloved, rotund captain in Pittsburgh.

At the end of the Seventies, Jim Rice seemed like the surest of sure things. Though he was a mediocre outfielder and though he struck out more than he walked, he was otherwise a complete hitter. In fact, from 1975 until 1980, he was the most complete hitter in baseball. He was the monster who crushed balls towards, onto and over The Monster. Rice was six foot, two inches tall and weighed two hundred pounds. Yaz was taller but grayer. Dewey was just as tall but much leaner. And Fred Lynn looked tiny next to all of them. But, to my young eyes, Jim Rice looked like the perfect slugger.

Until I saw him next to Dave Parker.

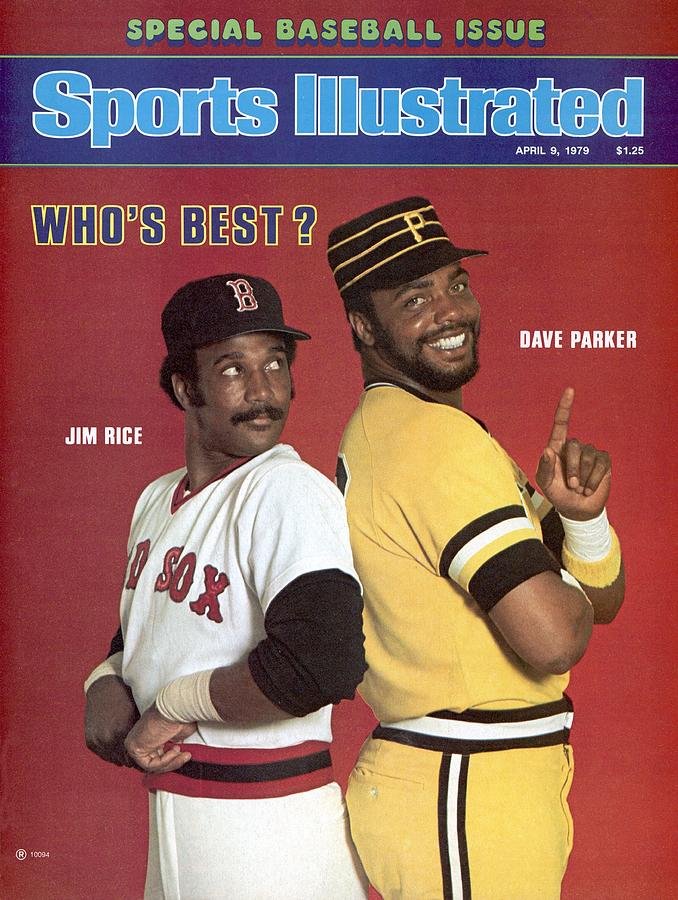

In the spring of 1979, Rice and Parker were featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated, beneath the headline “Who’s Best?” Parker towers over Rice in the photo. His chest bulges several inches beyond Rice’s modest pecs. On his own, Rice looks like a heavyweight prizefighter. But, next to Parker, he looks like Rocky standing next to Drago. The Cobra looks like he can swallow the tiny, reigning AL MVP whole.

That same year, Willie Stargell — Parker’s teammate — won the NL MVP (he actually shared it with Keith Hernandez) while The Pirates made their improbable run to the pennant and then through the mighty O’s to win the World Series. Stargell was thirty-nine that year, still able to muster thirty home runs but unable to play through a full season. In his prime, Pops was positively massive. His Baseball Reference page lists him at one hundred and eighty-eight pounds, which is one of sport’s greatest all-time understatements. The last time he weighed that was probably in high school. By the mid Sixties, Stargell was well over two hundred pounds. And the man who, in 1979, was as much mascot and coach as he was first baseman, looked to be at least two hundred and fifty pounds. Pops was a very big man. And yet, compared to Dave Parker, with whom he was frequently photographed, Willie Stargell looked like Santa Claus standing next to The Incredible Hulk.

Over the years, there have been many major league baseball players bigger than Dave Parker, who stood “merely” six feet, five inches tall. And surprisingly, Parker was never an elite home run hitter — his single season high was thirty-four. He is most certainly not the greatest player to have been omitted from the Hall of Fame — that would be Joe Jackson. And he is not the most famous one, either — that would be either Barry Bonds or Pete Rose. But for the better part of sixteen seasons, from 1975 through 1990, Dave Parker was as important as any player in baseball.

I say “important” not to diminish the greatness of his on field achievements. Parker was the 1978 NL MVP and league leader in batting average, slugging and OPS. He amassed over 2,700 hits in his career while maintaining a .290 average and while driving in nearly 1,500 runs. He finished in the top ten of the MVP voting six times and in the top twenty nine times. He was a three time Gold Glove winner and two time World Series champion. At his very best, and in spite of his massive frame, he swung the bat more like Tony Gwynn than like Reggie or Rice or any of his closest peers. He had a cannon for an arm and, in his twenties, could run like a tailback. The Cobra was a throwback to Willie and Hank in that he was — once upon a time — a true five tool player.

And he knew it. Parker’s idol was not Mays or Aaron or, even, Roberto Clemente (his former teammate). His hero was The Greatest — Muhammad Ali. Young Dave Parker was convinced of his own preeminence and, like Ali, would advertise it in rhyme. Parker used to say “When the leaves turn brown, I'll be wearing the batting crown.” He was fast and strong, like The Champ, but also, he was massive and intimidating. If, in 1978, he was the Ali of baseball, he was also its George Foreman.

On June 30, 1978, in the midst of his most dominant season, and having just hit a triple, The Cobra was barreling home towards Mets’ catcher — and generally immovable object — John Stearns. Amazingly, Stearns held onto a throw to the plate and Parker was called out. But not before the catcher was concussed and Cobra broke his cheekbone. Astonishingly, two weeks later, while chasing a division and a batting crown, Parker returned to the line-up wearing a very basic, entirely frightening, half white, half black protective mask designed for hockey goalies. In the one hundred and fifty year history of the sport, never has a more terrifying figure stood at the plate.

For several games, before he reverted to a modified football helmet to protect his broken face, Dave Parker looked not unlike Jason Voorhees dressed as a giant killer bee. And, in spite of that injury and the limitations of his serial killer costume, Parker went on to hit .334 with thirty home runs and one hundred and seventeen RBIs.

That offseason, the Pirates signed Parker to a five year contract worth more than a million dollars per year, making The Cobra the leagues highest paid player and most visible target. He finished the 1979 season tenth in the MVP voting and, more importantly, he and “The Lumber Company” brought the Pirates their first championship since 1960 (and their last one to date). Parker managed all of this — the MVP in ‘78, the batting crowns, the pennant and the title — while fully addicted to cocaine. Which is the other, and the no less important side, of this story.

Between 1976 and 1982, four years of prime and three of marked regression, The Cobra was a drug addict. Obviously, he was not alone. Baseball was full of addicts — alcoholics, pill poppers and, increasingly, cokeheads. It had been long suspected. The stories of “greenies” in baseball in the Sixties spared no one. Mickey, Willie, and seemingly half the all-stars in the league needed some speed to make it through the one hundred and sixty-two game slog. And, by the late Seventies, cocaine offered some of the benefits of speed, but with the perception of luxury and upward mobility. Cocaine was the drug for rich people. And Dave Parker was rich.

Cocaine also worked — until it didn’t. After years of a reliable .320 average, twenty-five homers and one hundred RBIs, Parker noticeably slumped. His waist bulged. And, soon, he could not stay healthy. He cleaned up in 1982, but it took two more years, and a change of scenery for The Cobra to return to form. By 1985, Parker was an MVP candidate again and a venerable leader for the insurgent Cincinnati Reds. But he was also on the brink of a very messy, very complicated reckoning.

That year, at the very height of his return to form, Parker was identified in commissioner Peter Ueberroth’s investigation as one of many ballplayers who had taken or trafficked cocaine. There were dozens of other well known players involved. But Parker was the star of the story, the main character in an unseemly tale about dugout coke sessions and airplane and hotel parties, torn from the headlines of Studio 54. The Cobra owned up to it — all of it. He named names. He described the highs and the lows. And, in return for a fine, community service and regular drug testing, he got off without a suspension. The next season, he was mashing again. Thirty plus homers. More than a hundred RBIs. Fifth in the MVP race.

By 1988, The Cobra had joined the Oakland A’s, where he served as elder statesman, mentoring the young Bash Brothers. For a while, it seemed like a happy ending was in store. The A’s won the pennant that year. The next year, they won it all. But, in between, The Pirates came calling. Or, more specifically, The Pirates’ lawyers came calling. Based on Parker’s admissions in the “Pittsburgh Drug Trials” of ‘85, the Bucs’ owners wanted their money back. Their reasoning was simple: they had paid millions for Dave Parker to try his best to continue to be Dave Parker. And, instead and by his own admission, they got a coke-added Cobra.

In 1989, Parker and his former team settled quietly out of court. That year, Parker finished eleventh in the MVP ballot. In 1990, as a DH for the Brewers, and at the age of thirty-nine, he hit .289 with nearly a hundred RBIs and finished sixteenth in the MVP race. Finally, in 1991, at the age of forty, having split the season between Anaheim and Toronto, Dave Parker called it quits. He’d began his career playing alongside Roberto Clemente and ended it alongside Roberto Alomar. Both of his teammates were first ballot Hall of Famers. Parker was not.

The case to admit Dave Parker to baseball’s Hall of Fame is pretty straightforward. His “counting stats” are consistent with the average Hall of Famer. The amount of black and grey ink on his resume exceeds about half of the club’s members. He’s got more than a handful of All Star appearances, two batting crowns, two rings and an MVP. And yet, The Cobra never received more than 25% of the vote share while his name was on the ballot, nor did he ever surpass 50% of the votes from the “Era Committee.” Parker is far from a “no brainer” selection, but, without question, there are many lesser and less important players in Cooperstown.

The case against Parker is more convoluted. Statistically, it relies on his relatively low WAR, which was depressed by two key factors: a relatively modest on base percentage and consistently negative defensive WAR (dWAR). The former I cannot contest — The Cobra was a free swinger. He never walked more than seventy times in a season, which depressed his OPS, a statistic of great esteem among advanced analysts. The latter, however, is a vulnerable case. Defensive WAR is far from an exact science. For example, both Jose Canseco, one of the worst defensive outfielders of his generation, and Chuck Knoblauch, a second baseman who could not throw the ball to first base, both have greater career dWARs than Parker, who was for a time known as a gifted outfielder with range and a deadly arm. I am not a statistician, but I’ve read enough to know that, among sabermetricians, there is rightful ambivalence about dWAR.

And so, if you discount the negative stats, which I suspect many voters have, then you are left with a “no vote” based either on Parker’s cocaine usage or his overconfidence. Both demerits feel ungenerous to the point of being racist. Drugs and alcohol have plagued baseball since the sport’s inception and, with the exception of performance enhancing drugs (which cocaine is not), substance abuse has never been the grounds for disqualification from the Hall.

As for his overconfidence — Parker’s was both deserved (which I guess, means it was not actually overconfidence) and a nod to his hero. Like Ali, The Cobra suffers from Parkinson’s disease today. Like Ali, he has tremors and aphasia. And like Ali, he is still a handsome, charismatic devil. Unlike Ali, though, Parker was never The Greatest. But, by any standard, he was truly great — one of the most important players of his generation and, for a couple of seasons, possibly the most important. He made his fellow sluggers — men who seemed like giants — look tiny. Moreover, there was that one time when he wore a black and white hockey mask to the plate just days after he broke his face and while on his way to a batting crown and MVP — a feat which has not been duplicated since.